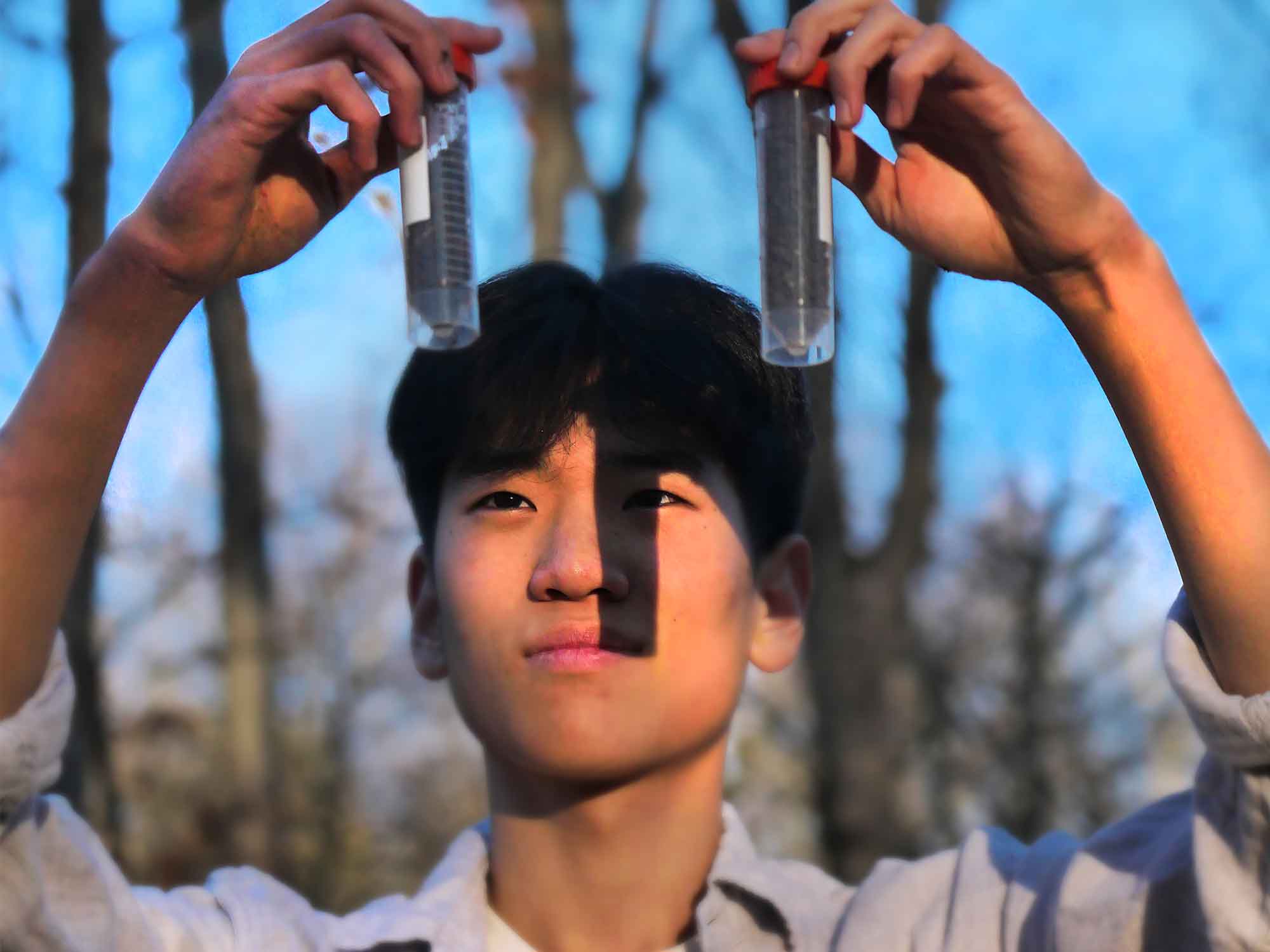

Many students might know John Jay High School senior Caleb Lee as a member of the varsity basketball team, president of the videography club or a musician who plays both guitar and piano. But Lee also has a deep passion for science. In fact, he’s wanted to pursue a career in the field since middle school.

Lee, who moved from New Jersey to South Salem at the beginning of his freshman year, always planned to take “a lot of AP science courses” in high school. But, during a meeting with his guidance counselor his freshman year, he learned about the school’s three-year science research program. Lee researched the program and decided to enroll. Then, a bit of luck set him on his path.

“The summer after my freshman year, my friend invited me to do a research internship,” Lee remembers. “He knew I liked science, and he’d found an internship that was looking into the science of grapes for growing wine at a nearby farm. I wasn’t really doing anything that summer, so I said I’d do it. My group was focused on the soil health of New York, how the climate affects it, etc.”

When his research class began that fall, he learned that he needed to find a mentor. Lee reached out to the staff member leading his research group, Richard Huh, the assistant farm manager at the Hemato Institute in Katonah. Huh said yes.

“I was really lucky,” says Lee. “Getting a mentor is probably one of the hardest parts of science research. Most students email a bunch of people who say no or don’t even reply. There’s lots of emailing until you find someone who would like to work with you. I was lucky enough to have already built a relationship with this guy, so I thought I would ask him. But I didn’t think he would say yes.”

Planting Seeds

From the beginning of the science research program, which runs from sophomore through senior year, students are expected to do their own research.

“The program gives students the opportunity to study something they’re interested in, in a scientific way,” explains science teacher Ann Marie Lipinsky, one of the program’s teachers. “They must conduct original research that hasn’t been done before. There are a lot of very science-based projects in fields like molecular biology and genetics, but from time to time, we’ve had behavioral projects and even some mathematical projects. However, the program is more about the process that occurs.”

“There are some rules guiding student research,” she continues. “So, for example, sometimes I have kids who want to try experimental surgeries on people, or they want to work with serial killers – that’s not okay. The teachers review all projects to ensure they meet guidelines set by the Society for Science/International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF) and the Junior Science and Humanities Symposium (JSHS). And any projects that involve human research are reviewed by an institutional review board.”

Students from all three grades learn and work together throughout their time in the program. Lee says that while the program is rigorous, the structure is fluid – a sophomore may ask a senior for help with their research, a senior may ask a junior to help them practice their presentation, etc.

According to Lipinsky, Lee has been “a delightful student.”

“He loves to learn, and he’s also very social, but in a positive way,” she describes. “So much of what they’re doing involves learning about other students’ projects and making the connections. It’s a tight-knit community of students who all have their individual projects, but they also support one another. As a sophomore, he was very open to working with some of the upperclassmen. And as a senior, he’s passing on that tradition of supporting the underclassmen by helping them and showing interest in their research.”

Breaking new ground

Lee’s experiment, titled “Experimenting with New York soil to determine the effects of using microorganism solutions and cover crops on soil health,” was designed to determine how to improve soil health. Because, as many farmers know, the healthier the soil, the healthier the crop (see page 58 for a more detailed explanation).

Lee chose to research whether planting cover crops (a plant that helps replenish the soil) or adding more microorganisms (a critical component of soil function and nutrition) could improve the health of New York soil.

“I studied different techniques that can improve soil health, and I knew wanted to do something with cover crops,” Lee explains. “I brought that idea to my mentor, and he said they were already planning to use cover crops, but he also wanted to try a microorganism solution. So, I researched that and learned it’s another technique that can improve soil health. We decided that instead of only testing one or the other, we could test them together to see how they affect the soil individually and when they are combined.”

Lee and Huh chose to use potatoes and daikon radishes for the cash crops (crops that can be sold) and buckwheat as the cover crop.

Due to last summer’s unexpected dry season and drought, they reduced the number of plots from seven to four, each with four beds. One plot served as the control with only the cash crops planted, the second included cash and then cover crops, the third featured cash crops and the microorganism solution, and the fourth had cash crops, cover crops and the microorganism solution.

Lee tested the soil three times (spring, summer and fall of 2022), measuring the levels of potassium, phosphorus, pH, nitrogen and organic matter. The results, he says, went against his hypothesis.

“I found that when the cover crops and microorganism solutions were combined, they were not as strong as they were apart,” he explains. “This was surprising, because, obviously, you would think that if they were combined, they would improve together. We’re not really sure why they didn’t, but it’s possible the cover crops removed certain aspects that the microorganism solution needs in order to flourish.”

Huh, who was impressed by Lee’s willingness to learn about farming and soil health, says Lee’s research will benefit the Hemato Institute.

“As a research institute, we’re trying a lot of new methodologies on our farm,” he explains. “We need to figure out the most effective form of farming for this region. With Caleb’s interest and drive to push this research forward, we now have this quantitative data that can help us understand a more effective way to approach farming in the future. We’ll continue his research because we want to understand how this will help our environment and our land five and 10 years from now.

Digging in

Lee says the science research program has taught him much more than how to conduct scientific research. He’s gained leadership skills, confidence in public speaking and learned how to read and understand scientific research. And he’s also learned the importance of balancing his workload (something he admits he didn’t do well during this course).

“My favorite part was the experience of carrying out my own research,” he says. “For the first time in my life, I accomplished something that I worked at for multiple years, and I can present it to other people. It’s something I can be proud of in my future.”

But that’s not the only high school experience that’s shaped him. Lee credits the Junior State of America Club, where he serves as treasurer, for opening his mind to others’ opinions. (The club “debates current events and other things that go on around the world.”)

“I’ve realized that talking with other people is a great thing,” he says. “I enjoy getting to hear other people’s opinions, and sometimes they can change my opinion. While I don’t really know if it’s something I would pursue in the future, it’s made me realize that people aren’t listening to each other’s opinions enough, and that’s something that can benefit me even more.”

But Lipinsky, who taught him all three years of the science research program, does see a future where Lee combines his passion for science with his people and debate skills.

“I would love to see him take a lot of his practical knowledge and be involved in policy, either at state or at federal levels,” she says. “We need people who understand and can propose important legislation that will protect our land and our soil – it’s a very vital natural resource. I can see Caleb making a really strong case for better practices.”

This fall, Lee will be a freshman at Cornell University in their College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. While he’s still figuring out his career path, he hopes to continue learning about and researching new strategies that can improve farming and the environment.

“I might want to consult with farmers, helping them plan out their seeding ratio, when and where to plant crops, or whatever they need help with,” he says. “I can see a future where farmers are scientists and scientists are farmers, and I think that could be a great world to live in. I think we could live in a world where the environment is really good, and crops are still being produced at a mass amount while continuing to improve the soil health.”

This article was published in the March/April 2023 print edition of Katonah Connect.

Photography by Justin Negard.

Gia Miller is an award-winning journalist and the editor-in-chief/co-publisher of Connect to Northern Westchester. She has a magazine journalism degree (yes, that's a real thing) from the University of Georgia and has written for countless national publications, ranging from SELF to The Washington Post. Gia desperately wishes schools still taught grammar. Also, she wants everyone to know they can delete the word "that" from about 90% of their sentences, and there's no such thing as "first annual." When she's not running her media empire, Gia enjoys spending quality time with friends and family, laughing at her crazy dog and listening to a good podcast. She thanks multiple alarms, fermented grapes and her amazing husband for helping her get through each day. Her love languages are food and humor.