Artist and Broadway Royalty Oscar Hammerstein merges ocular neurology and color theory with his family’s legacy.

The solitude of a professional artist and the spotlight of musical theater may seem like two lives at odds with each other, but for Oscar Hammerstein III, it’s the perfect combination. Growing up in a family of performers (yes, his grandfather was Oscar Hammerstein Jr. of Rodgers & Hammerstein fame – the family name skips a generation), Hammerstein was the odd one out. From an early age, he demonstrated a proclivity for visual arts.

In kindergarten, when children typically draw stick figures, Hammerstein (called Andy as a child) was already drawing people doing backhands with a tennis racquet. By age 10, he was a regular at Manhattan’s famed Art Students League. And by the time he was in sixth grade, his elementary school changed its rules and gave him a one-man show.

“I was making art outside the box – painting these sort of spermatozoa with eyes and smiles, and my teachers were very, very supportive,” he remembers. “They had never called attention to art before, but they decided to put my art in the main hall and do a little wine and cheese sort of thing.”

Hammerstein continued to pursue art throughout high school, but when it was time for college, he pondered studying for a “normal” profession. Yet his father, who was always supportive even though he didn’t quite know what to do with a child who was interested in fine art, thought otherwise.

“I would say I needed a real job, but he would say, ‘why not just stick with what you’re doing,’” Hammerstein remembers. “He was a weird, weird father. He didn’t want me to be a doctor or a lawyer. But the reality is that no one in my family has held to a real job in five generations – not even a dry cleaner. My father was a director, my mother was an actress, my stepmother was an actress and my other stepmother was an actress. My uncle was a producer, my grandfather was a lyricist, and his father was a vaudeville manager. Their cousin was a silent movie screen star. And the patriarch of the whole bunch was an opera impresario. We just can’t hold a regular job.”

But Hammerstein tried anyway. He began college as a marine biology major, yet after a few months, he realized his heart wasn’t in it – he just wanted to make art. However, what did fascinate him were color theory and ocular neurology, and they set him on a distinct artistic path.

“I studied pattern recognition – looming rods and cones in the eyes,” he explains. “In the 70’s there were a bunch of great writers who helped me understand what I was seeing. What happens to your eye when you go from light to shadow? What changes? Can you paint without black and white?”

Understanding these concepts played a huge role in the art he began to create. He went from an artist who drew bodies, which isn’t easy (“noses, and fingers and toes are very hard to draw”), to exploring how we see color.

“For the longest time, I tried my best to avoid the use of pure black and pure white,” he remembers. “I studied [Johann Wolfgang von] Goethe’s color theory, and I’ve tried to apply it to my paintings over quite a period of my life. I found that there’s a certain intensity that came with juxtaposing things, like yellow against purple, that you couldn’t get from white and black. It just seemed bloodless compared to what you could do with actual primary colors. I still spend some time in thought dealing with how colors interact with colors, as opposed to black and whites.”

Hammerstein began a series of work that he still produces today – Sunspot Abstracts, based upon what happens when you look directly at the sun. He says there’s a geometry in the image burned into the retina. While he originally believed he was organically painting spots on canvas, he eventually realized there was a pattern. Later, he discovered a simpler way to capture that pattern, and 35 years later, he still creates these works.

“It’s actually a theme that doesn’t go away,” he says. “I’m staring at four of them now. I can’t get rid of them. The spots are everywhere!

“But there’s a certain premise to them,” he continues. “There’s a geometry and a logic. My job is to hide that logic in plain sight, to do stuff to the rest of the canvas that makes people not see what’s clearly in front of them. That’s the game I play. And there’s no limit to the number of ways in which you can distract people from the spots. What I’m doing more than anything is a playfulness.”

To create the foundation for his paintings, Hammerstein uses an oil-based ink. He paints the spots and then “pulls them off with acetone and other toxic chemicals.” Sometimes he’ll use acid to burn parts of the spots while other times they’re distressed or disappear completely. However, the overall geometric structure remains the same.

“I like being able to go back and forth from putting paint on to taking paint off,” he explains. “I’m not just a painter, I’m also an erasist.”

After college, Hammerstein lived an artist’s life in Manhattan, making ends meet with odd jobs like moving furniture, as well as some regular work for “Saturday Night Live,” colorizing and stringing photographs together to create animated shorts for guests like Steve Martin, Billy Crystal and John Belushi.

During this time, he ran into a friend he’d met four years earlier – Jennifer. The day he’d first met her in college, he turned to another friend and said, “That’s the woman I’m going to marry.” But she was younger and had a boyfriend. He graduated, moved to the city, and thought nothing of it until he ran into her that day several years later.

“I remembered what I’d said and decided that now I’m going to do it,” he recalls. “We dated for about two years and got married.”

They now have three adult children – Dashiell who is a composer, Grace who works in post-production and Jackson who lives in Montana as a property manager and cowboy. Hammerstein broke the family tradition of multiple marriages – they’ve been married for 36 years. But along the way, he did pause his art to pursue his family’s legacy.

“When I was about 30 years old, I was reading about my family’s history, and I needed to know more about my great, great grandfather, the magnate who started the business,” he remembers. “So, I approached the family company, which I’d never worked for, and said, ‘I’m going go to the Library of Congress to do some research on the family.’ Eventually I began to do little, tiny talks. Then that small lecture series got out of hand, turning into the other half of my life. I guess I sort of stumbled backwards into the theater.

“I didn’t have any other life ambitions until I stumbled across my family’s history,” he continues. “I am the first child of a chorus girl marriage, and I was not really held in high esteem by my aunts and uncles. So, the idea of me learning about my family history was not something I got from them – I got it despite them, sort of. I found a calling: I became a public speaker and a historian. But not because anybody supported that. It was my way of claiming what I could claim.”

In 2010, Hammerstein wrote a book entitled “The Hammersteins – A Musical Theatre Family,” and he began lecturing. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, Hammerstein lectured every other month. But his bookings were usually done a year in advance, because when you’re a Hammerstein, you can’t just give a lecture, you must give a performance.

“The basic problem with my lectures was that someone would say, ‘well, we’re gonna put it to music,’” he says. “And then they’d say, ‘and we’ve got to get some singers, so we really should get some instruments. Actually, let’s get an orchestra.’ And because the orchestra needs six months to a year’s worth of lead time for rehearsal, I booked a year out. In general, I barely know what I’m doing in a year’s time. But I know I’m doing a lot.”

As we emerge from the pandemic, Hammerstein’s talks have slowly begun to resume. These lectures help support his career as an artist. And as a self-described introvert, they also give him an opportunity to step outside his shell.

“I get it all out of my system on one day,” he jokes. “All my socializing happens in one day, and then I’m back to being a hermit in my studio.”

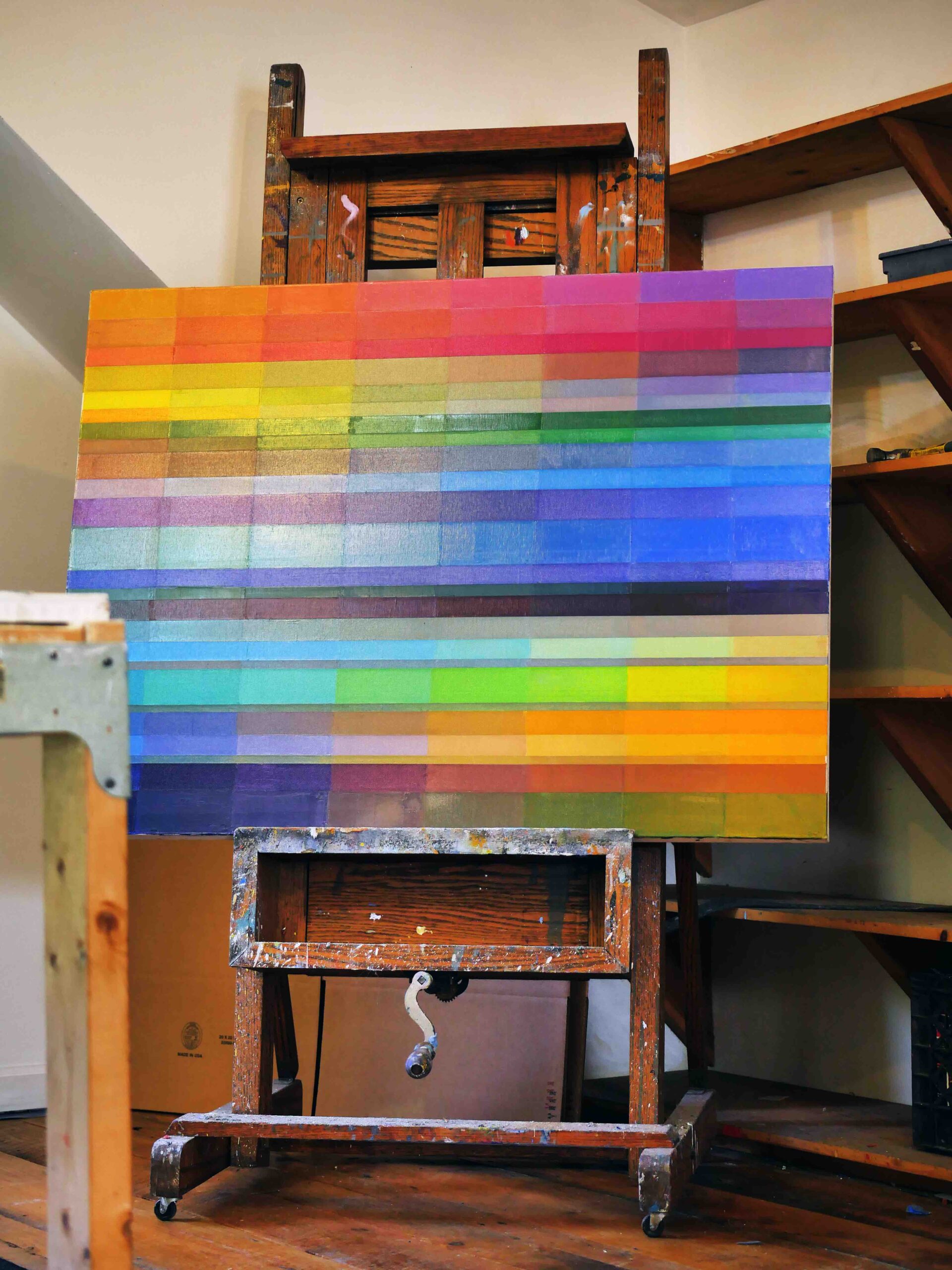

During the past several years, Hammerstein has continued to paint his signature Sunspots, but he’s also begun a new series called Tempo Clash, inspired by his love of piano, which he plays every morning before he begins painting.

To do this, Hammerstein begins by painting a square from left to right, moving along through time. Then he explores what the basic rhythm would look like if he overlaid it with another rhythm that fit into the same space but was cut differently.

“Instead of eight to a bar, what if it was 15 to a bar, or seven to a bar,” he explains. “Then I’d look at what eight and 17 look like together. And usually, that makes this completely different pattern. Over time, I’ve figured out that you don’t want to use an odd number with an odd number because it’s too symmetrical. And you don’t want to use an even number with an even number because it’s too repetitive. So, you end up with juxtaposing an odd number with an even one. And that has yielded all my paintings.”

To the untrained eye, paintings in the Tempo Clash series may look like piano keys, but Hammerstein emphasizes that they’re not. They’re the visual representation of music.

“They’re very pleasant,” he describes. “And they actually vibrate when you look at them. Well, if I get lucky, they vibrate. They come off the page like some strange carnival act. But it works every time these days because I’ve started to really hone in on that aspect. You can pick pink and purple and there’s a small distance of where the colors can go, or you can pick orange and blue, and there’s a huge distance that the colors can go. So, you can be subtle, or you can be loud. And lately, I’ve been loud.”

It all goes back to ocular neurology and color theory – the two main influences of Hammerstein’s work. And yet, over time, they’ve translated into a very different series of work.

“These days I’m either painting space over time, as in looking at a sunset over a period of time and capturing the space of that sunset, or I’m doing time over space where I’m applying different rhythms to the same space and seeing what third pattern emerges. So, it’s time and space. It seems like a pretty bland artist’s statement, but that’s what interests me.”

This article was published in the July/August 2022 print edition of Katonah Connect.

Gia Miller is an award-winning journalist and the editor-in-chief/co-publisher of Connect to Northern Westchester. She has a magazine journalism degree (yes, that's a real thing) from the University of Georgia and has written for countless national publications, ranging from SELF to The Washington Post. Gia desperately wishes schools still taught grammar. Also, she wants everyone to know they can delete the word "that" from about 90% of their sentences, and there's no such thing as "first annual." When she's not running her media empire, Gia enjoys spending quality time with friends and family, laughing at her crazy dog and listening to a good podcast. She thanks multiple alarms, fermented grapes and her amazing husband for helping her get through each day. Her love languages are food and humor.